Harvard University is helping to lead the way in biofertilizer development, putting faith in its own science and converting the campus grounds to a nitrogen-fertilizer free-zone. In doing so, the university hopes to keep spaces green while lessening the negative impact of plant nutrition on the planet’s rivers and lakes, and especially ‘dead zones.’

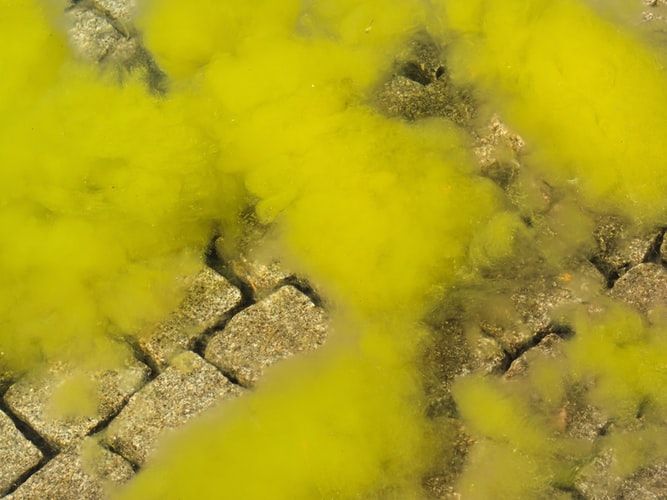

As the journal Scientific American explains, “So-called dead zones are areas of large bodies of water - typically in the ocean but also occasionally in lakes and even rivers - that do not have enough oxygen to support marine life. The cause of such ‘hypoxic’ (lacking oxygen) conditions is usually eutrophication, an increase in chemical nutrients in the water, leading to excessive blooms of algae that deplete underwater oxygen levels. Nitrogen and phosphorous from agricultural runoff are the primary culprits, but sewage, vehicular and industrial emissions and even natural factors also play a role in the development of dead zones.”

Harvard researchers felt increasingly touched by the impact of conventional fertilizers, especially when reading of how many dogs die each year from swimming in ponds and waterways poisoned by toxic blue-green algae. They decided to act and set themselves a goal of converting the campus to a nitrogen-fertilizer free-zone.

To achieve this, they plan to use a new biofertilizer developed by Harvard’s own Prof. Daniel Nocera; a product which works using only sunlight, water, and air. A fertilizer that not only remains in plants, potentially year after year, but one that even absorbs carbon dioxide from the air making it available for plants in the soil. With one simple switch in fertilizer, the hope is to have bigger, healthier plants while at the same time helping to clean waterways and combat climate change.

“Using the new biofertilizer methods across the U.S., we could remove significant amounts of CO2 per year by sequestering the carbon in the soil,” says Dilek Dogutan, a principal research scientist in the Nocera group who is heading the initiative.

Dogutan already knew that the biofertilizer had been proven effective in test conditions on radishes grown in a greenhouse, but wanted to test the fertilizer product outside. It was only when she got an email from the President's Administrative Innovation Fund (PAIF) that she saw the opportunity to test the biofertilizer outside her office window.

“We wanted to take the research out of the controlled environment,” says Dogutan, “to see the effect of soil acidity, air, temperature, humidity, everything.”

To do that, she teamed up with Quentin Gilly, the manager of laboratory sustainability and Paul Smith, the associate manager of landscape services to devise an application plan.

While at present, the university is working towards a transition to 75% organic fertilizer use by the year 2020, the team were aware that organic fertilizers can still flow into the local water system, contributing to algal blooming.

To combat this a switch to a biofertilizer product was needed, and the Nocera group had the perfect product.

As the Harvard Gazette explains, “Invented in 2018, the biofriendly fertilizer relies on an engineered cyanobacteria called Xanthobacter autotrophicus. The invention incorporates years of research, going back to Nocera's artificial leaf technology, which splits water to make hydrogen and oxygen, performing photosynthesis better than any leaf.”

The result is a biofertilizer product that has less impact on the environment that other fertilizers.

“The new treatment uses the hydrogen from water splitting and combines it with nitrogen in air to produce ammonia, which plants can absorb into their roots. Since inorganic and organic fertilizers often give plants more nitrogen and phosphorous than they can use at one time, the excess gets washed away. But the biofertilizer stays safe within the plants’ roots, stored for future use.”

The next step is to use the university funding to perform large-scale tests across the campus from winter 2020 through until autumn.

However, earlier test patches on two ‘parking spot-sized’ spaces have already given very positive feedback. As the scientific journal Phys.org reports, “In one, Daniel Loh, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Chemistry, planted radishes, turnips, and spinach in each. Then, every week, he fertilized one with 100 milliliters of the engineered cyanobacteria mixed with water and sprayed it over the plants. The other plot got just as much water, without the bacteria.”

The growers then monitored the plants and collected data on the condition of the soil.

“Loh’s measurements showed that not only did the biofertilizer help his plants grow larger than those in the unfertilized plot, the bacteria did not leech into the surrounding plants.”

As Loh states, “Nutrients are taken up by plants before they can diffuse large distances.”

This led the team to set up a company called Kula Bio to help commercialise the fertilizer without even waiting for the campus results. This new business has already arranged for further trials off campus and has been able to price the product at the lower end, so as to attract growers away from conventional fertilizers.

Meanwhile, analysis continues to better understand the relationship between the microbes and the plants.

“This is still very new research,” notes Dogutan. “We are still trying to figure out the details: the loading, the sequence, maybe we need to design the bacteria in a different way.”

For while the team is hopeful for their new business, they are less focused on making a profit as in helping the environment.

As Dogutan states, “We have to do something because, really, we're destroying the world. Coming to work every day is great, but what is our higher purpose? It's not just sending those emails. The higher purpose, at least for me, is giving back to the Harvard community the best way that I can.”

Perhaps the biofertilizer industry should also listen to this ideology. Making biofertilizer has a greater cause than just as a business. Instead it is about change agriculture for the better; slowing down climate change and helping to keep the oceans and rives clean for wildlife. But then you probably don’t need to go to Harvard to know that.

Photo credit: Guardian, Harvardnews, Harvardmagazine, Semanticsscholar, & Lecomtedominique