Most brand new industries involve intense races to be the first to bring products to market. Tesla is in fierce competition against Ford, GM and many others to make the first affordable electric, self-driving car. Microsoft famously beat Cisco and IBM to market with a number of features for home computers, whilst Sony made a small fortune producing portable music in the Sony Walkman, until the technology was copied by other manufacturers.

However, a biofertilizer project in Tuscany has taken on a different approach for the expansion of its plant nutrition products. Instead of hiding the recipe for quality biofertilizer, they are instead expanding a network of crop nutritionists, farmers, and fertilizer suppliers to share information and spread the word of the advantages of biofertilizer.

“Biofertilizers,” are defined by researchers on the scientific journal Research Gate as, “natural fertilizers of living microbial inoculants of bacteria, algae, and fungi, alone or in combination, which augment the availability of nutrients to plants. The role of biofertilizers in agriculture assumes special significance, particularly in the present context of increased cost of chemical fertilizer and their hazardous effects on soil health.”

The lead in cooperation in the biofertilizer industry is being taken by FERTIBIO, which is co-funded by the EU Commission, and described by European Innovation Partnership (EIP-AGRI) website as, “… an Italian Operational Group using microorganisms and biomaterials to develop innovative biological fertilisers for the cultivation of food and feed crops.”

The desire to share growing successes and failures with others is based upon the need to lower the use of mineral fertilizers and lessen environmental pollution. At the same time, the highly agricultural Tuscan economy requires that crop productivity, soil fertility, and production quality are all maintained.

The appetite to move away from conventional fertilizers is a trend that is being seen across all levels of agriculture, as well as among consumers.

As Cosimo Righini, an agricultural researcher from the University of Pisa and a representative of CIA Toscana, one of FERTIBIO’s many partners notes, “In Tuscany and across Europe there is growing interest in new models of agriculture that guarantee a reduction of pollutants and a rationalisation of energy inputs.”

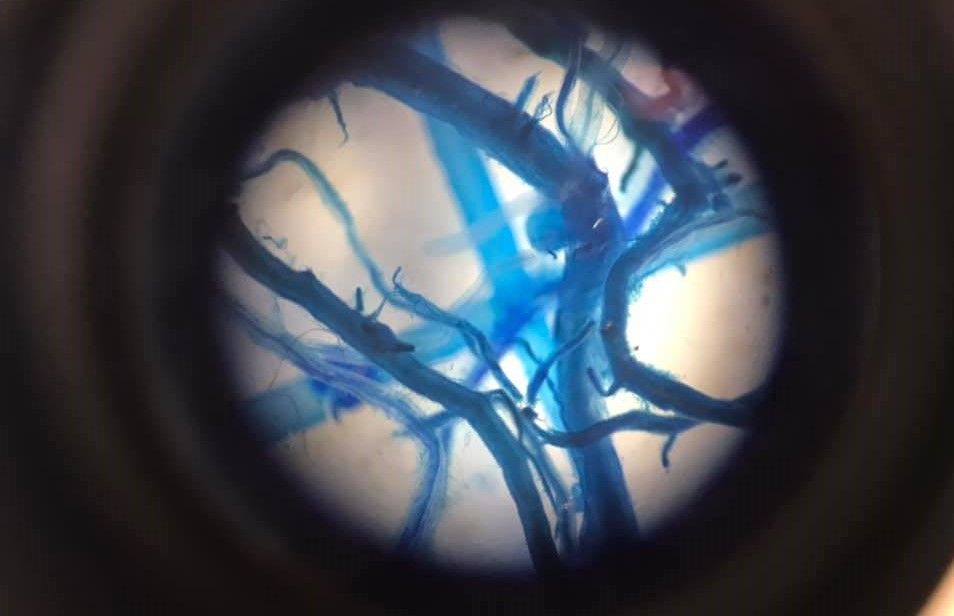

The goal is to focus on ‘Symbiotic Agriculture’, a crop nutrition system which he describes, “… is about restoring, safeguarding and using the symbioses between soil microorganisms and the root systems of crops. Biofertilizers help to achieve this symbiosis, accelerating microbial processes which increases the availability of nutrients.”

At the heart of the project are the farmers, who work in an agricultural cooperative to help develop and test new formulations of biofertilizers for herbaceous plant species. For the FERTIBIO project, this means carrying out field tests in different parts of the region and with different crops and cultivation systems.

These tests are largely focused on the gradual release of soilborne microorganisms called arbuscular endomicorrhizal fungi or AMF.

“We are collecting interesting results about the application of AMF in tomato production” says Elisa Pellegrino PhD, an Assistant Professor at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, “some cultivars seem to be influenced in a positive way in their growth and ripening”.

In fact, most farmers notice a positive effect from the use of biofertilizers.

“Biofertilizers increase yield by 15-35% in most of vegetable crops,” says Pellegrino. “Some excrete antibiotics and thus act as pesticides and, more importantly, they do not cause atmospheric pollution and increase soil fertility compared to mineral fertilisers.”

Once all field tests are complete the project will then transfer to an industrial scale. “One of the project goals is to scale up production of different types of biofertilizer at an industrial level,” says Righini, “doing this will create the first Tuscan production of biofertilizers developed together with farmers.”

At the core of the growth in production and application will be the sharing of the benefits of biofertilizers, aiding farmers in their own trials, educating them with training courses and workshops, as well as the publication of a field guide on the use of FERTIBIO’s specific biofertilizer products.

As Righini makes clear, “We are strongly interested in creating a network on biofertilizers, with the help of EIP-AGRI to share projects and best practice.”

That in itself sounds like best practice for the whole biofertilizer industry.

Photo credit: Facebook