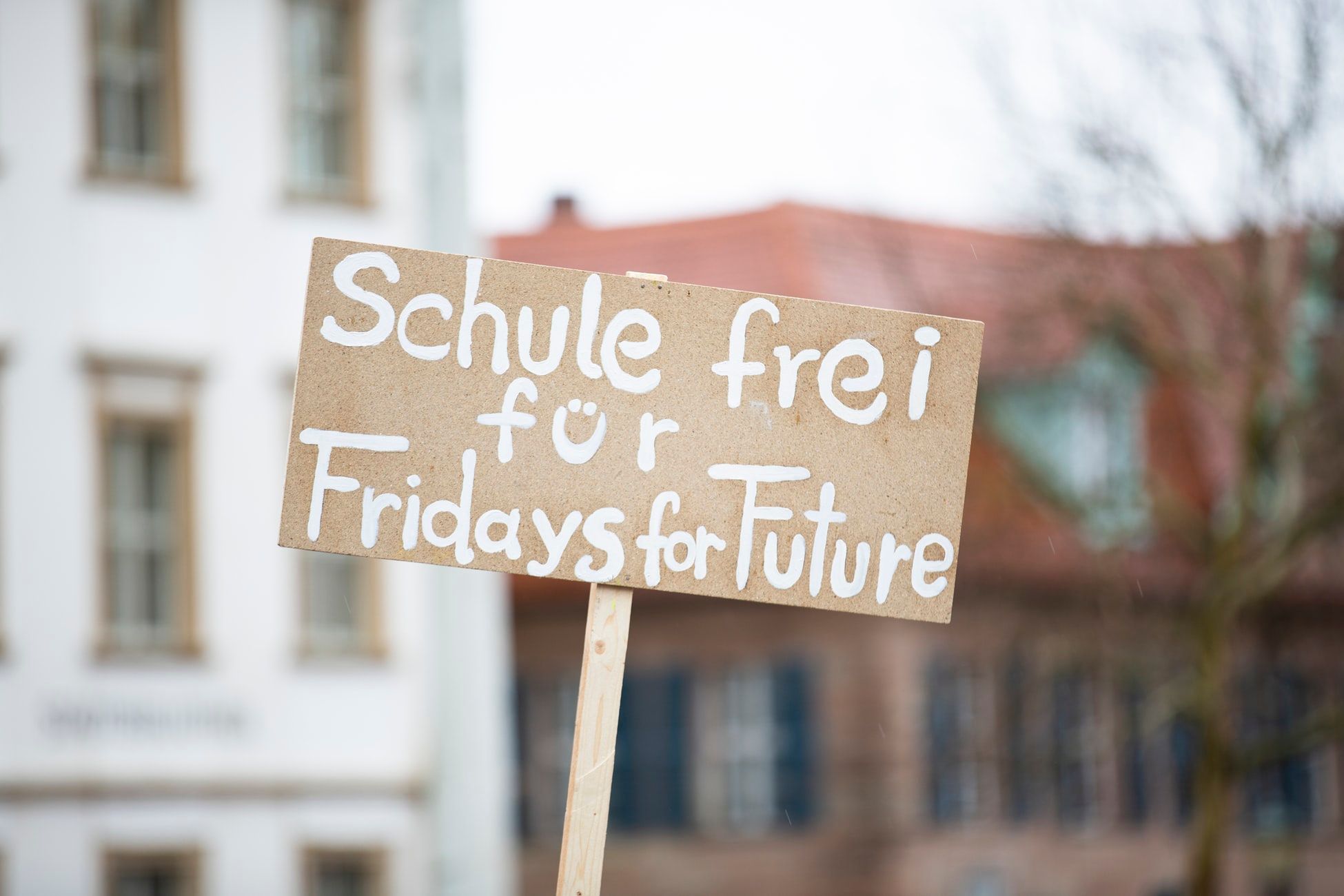

The world was watching recently as the climate change strikes and marches went global, with millions of schoolchildren protesting against the continued burning of fossil fuels, and the political and economic failure to reduce CO2 emissions.

It was a defining moment for a generation.

But beyond the packed masses and the placards, behind Thunberg’s heartfelt pleas to the UN general assembly, a quieter action against climate change is happening.

Just outside the fields of the Nile valley, a tech-based start-up is making an impact in local agricultural with the bio-fertilizers it is producing.

While the news will not make the front pages of any national newspaper, it is a signal of the slow shift of the fertilizer industry away from agrichemical products to a more sustainable, locally sourced, and low-emission crop nutrition solution.

The company is called Baramoda, and produces, “… organic fertilizers for different types of soils and agricultural products, the aim being to replace chemical fertilizers and decrease excessive usage of water, both agricultural practices that are common in Egypt.”

With an overall aim, “… to provide innovative solutions to maximize the efficiency of agri-waste management which is estimated at 38 million tons per year with only 12 percent going through a recycling process.”

Founded by Mostafa el-Nabi, Moussa Khalil, and Mohammed Abu Zaid in 2018, the entrepreneurial team is keen to revolutionise the local sugar cane and sugar beet industry with innovation that will help decrease farming costs without damaging the soil. A tactic that will provide more benefit to reducing climate change emissions than any speech at the UN.

According to Salma Shaker, the marketing manager at Baramoda, “5,000 tonnes of fertilizer have already been produced in the company’s factory.” A small start, but an amount that has facilitated the cultivation of 1,387 acres of farmland.

But beyond the teetering first steps of this young fertilizer business, lies a national goal. As the Organic Agriculture Laboratory of the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture reports that, “While Egypt is seeking to expand its agricultural production, there is still a shortage of available fertilizers, whether they be chemical or organic. The annual demand for organic fertilizers in Egypt is estimated at 60 million tons, with current supply standing at around only 33 million tons; a deficit of 27 million tons.”

In June 2019, the chemical industry journal C&EN reported that, “The Haber-Bosch process [at the heart of industrial fertilizer production] represents a huge technological advancement, [but] it’s always been an energy-hungry one. The reaction, which runs at temperatures around 500 °C and at pressures up to about 20 MPa, sucks up about 1% of the world’s total energy production. It belched up to about 451 million t of CO2 in 2010, according to the Institute for Industrial Productivity. That total accounts for roughly 1% of global annual CO2 emissions, more than any other industrial chemical-making reaction.”

To combat this, a series of smaller start-ups, like Baramoda, are taking the need for change to the farmers in their fields. Unlike the mega-chemical facilities, Baramoda and others like it, has a team of only 20, but has a long-term goal to meet the challenges of feeding a growing population. As El Nabi notes, “Egypt’s population is expected to increase to 120 million by 2050, so preserving the country’s natural resources is very important to ensure food security.”

Feeding the population is a key role of any government, and parliament has already enacted numerous laws and agricultural initiatives aimed at increasing food production, while maintaining soil health. For example, the ‘One-and-a-Half-Million Acres’ project is supporting local farmers on land reclamation, sustainable fertilizers, soil nutrition, and limiting water usage. It aims to provide employment, meet local demand for produce, as well as increase exports.

Alongside state funds, private investors are seeing the cost advantages of smaller, more-ecological fertilizer businesses. The US$5 million seed investment for Baramoda was supplied by angel investor Khaled Ismail, who foresees the challenges that climate change will have on agriculture.

Limited more, more expensive water, carbon taxes, government restrictions on non-circular economy products, and the closure of factories with high-CO2 emissions are already taking place in different parts of the world. This combined with increased demand for food and farm inputs, makes the biofertilizer industry a sector full of potential.

Like many in the fertilizer industry, they see the benefits of locally sourced nutrition, made near the farms where it will be used. Biofertilizer production for niche markets, where the business can specialize in specific crops and soil types with low overheads and short supply chains.

While the world will always remember Greta Thunberg and the recent Climate Change protests, it may be organic fertilizer entrepreneurs and investors in biofertilizer technology that could be the real heroes in saving our planet’s ecosystem.

Photo credit: IrishTimes, Egyptianstreets, Worldfertilizer, Looklex, & Agora